Kolaj #17 Editorial

Cut It Out

Can we stop thinking of collage as a “bastard form”?

One of the things that makes collage, as practiced today, uniquely modernist is the fact that a collage always references itself.

Consider a pre-modernist painting. The goal of a traditional painter is to so well render the image that the act of painting disappears and the viewer is allowed to become immersed a fictional dream. A bad brush stroke, a poorly drawn face, or awkward trees do not serve the painting, they distract the viewer from the experience the artist intends. For most of art history, this was the paradigm. Modernism was the ultimate disruption. As Clement Greenberg put it, “The essence of Modernism lies, as I see it, in the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself, not in order to subvert it but in order to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence.” To this end, the modernist painter used bad brush strokes, a poorly drawn faces, and awkward trees to remind the viewer that they are looking at a painting, to ask the viewer to contemplate the artifice of the discipline, of the medium, and to delve into the ideas, feelings, and experience behind it.

By its nature, collage has always done this. One cannot look at a collage without acknowledging that the fragments are artificial and in conversation with each other. This is sort of the point of collage, to reference itself. Or, as Francisco J. Ricardo, writes in Cyberculture and the New Media, “We might consider collage as not-painting, but it is not sculpture, either; its coarse, uneven tatters, cementations of more than immediate expression, announce the commanding plan of bastard form, and thus the cacophony of a staunch anti-formalism. As neither painting nor sculpture, collage could be inaugurated as the first new art medium of 20th century sensibility.”

And yet, given collage’s epic role in modernism, it perseveres as a “bastard form”. On numerous occasions in the pages of this magazine we have highlighted the lack of curatorial regard, critical writing, and basic attention to the medium. On the website of The Guardian, the respectable UK publication recently ran a collection of collage as a way of highlighting Thames & Hudson’s new book, Cut That Out. (The 288-page book offers what the publisher calls “The very best in contemporary collage by 50 of the world’s leading creative studios and graphic designers.”) The Guardian titled their piece “Can they cut it? The artists making collage cool again–in pictures” which we found stupid for a number of reasons. It goes without saying that we feel collage is, was, and will always be “cool” and not simply a passing fad that needs to be revived every few years. Cut That Out is not an awful book, but it is most useful as decoration for a design firm’s waiting room. It has no critical value and contributes little to understanding the medium. And therein lies the problem when collage crosses the minds of editors and exhibition programmers. “Let’s have a show about collage” is as brilliant a curatorial statement as “let’s show some paintings” and yet, nothing seems to stop a parade of exhibitions titled “Cut and Paste” from crossing our desks. (And that is not to dismiss the very valid exercise of exhibiting a group of collage artists. Collage is, in addition to a medium, a movement, a community, and group shows are how we come together.)

So enjoy this issue of Kolaj Magazine. It is the start of our 5th year of publishing the magazine and we are redoubling our efforts to stem the wave of dull-witted discourse about collage. Through the investigation of taxonomy, critical reflection on artists’ work, and articles that explore the influence of collage on other mediums, we hope to be a voice for this “bastard form” until we stop treating it as such.

—Ric Kasini Kadour

This editorial appeared in Kolaj #17. To get your own copy, SUBSCRIBE to Kolaj Magazine or Get a Copy of the Issue.

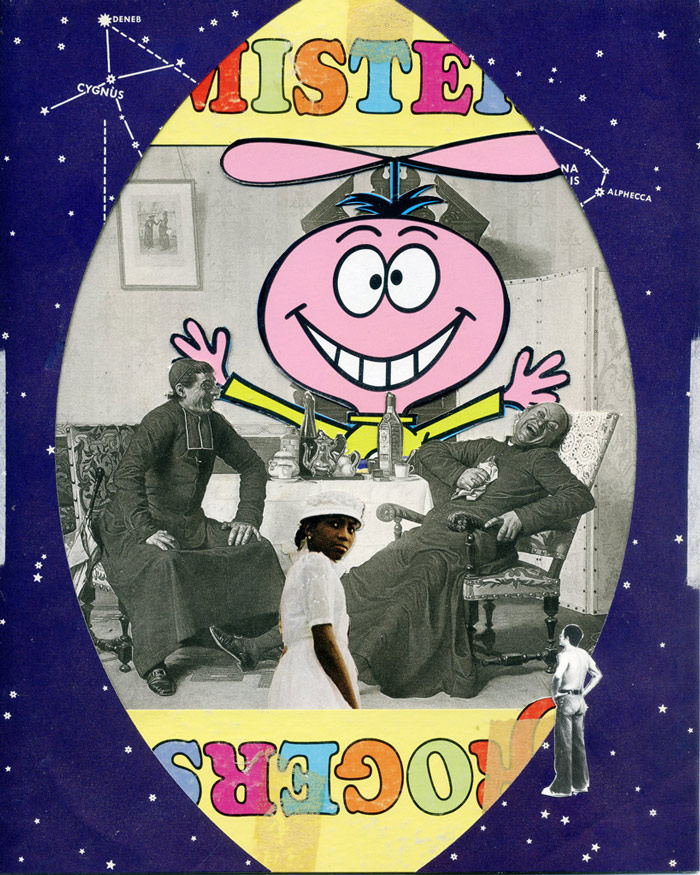

Image:

c231 Seriously?

by Mister Koppa

10″x8″

19th century photogravure print of the painting A Good Story by Leo Herrmann, commercially printed book and magazine (National Geographic) paper, compact disc insert (“The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”, Genesis), record album (“A Place of Our Own”, Mister Rogers), Quisp cereal box board, and acid-free permanent adhesive

August 2016