Collage in the Service of Rebellion or We Are Only in It for the Money?

by Edvard Derkert

Collage is a fast, destructive and irreversible art form, as if it was made for blackmailers and iconoclasts who use a pair of scissors as their weapon. When the sharp knife pierces into the thin tissue of the paper, holes and gaps appear in its tracks, ideological and cultural cracks, dislocations and distortions. With resolute cuts, inner organs, plumbing tubes, house facades, or smiling mouths are removed from their contexts. Destroy, isolate, and abduct is the first command of collage. The second one is to wed oil with water: the aesthetics of opposites.

Collage willingly lends itself to rebellion and resistance. The cuts of collage turn downside up, high goes underground, beautiful turns ugly, and the common gets the crown. Everything is possible! These radical cuts appeal to the impatient: Everything at once. Revolution here and now. Just after the First World War, Dada revolted against the political and spiritual barbarity of Western civilization and its petrified bourgeois art. All that was needed was a stack of magazines, a pair of scissors, a knife, and a pot of glue.

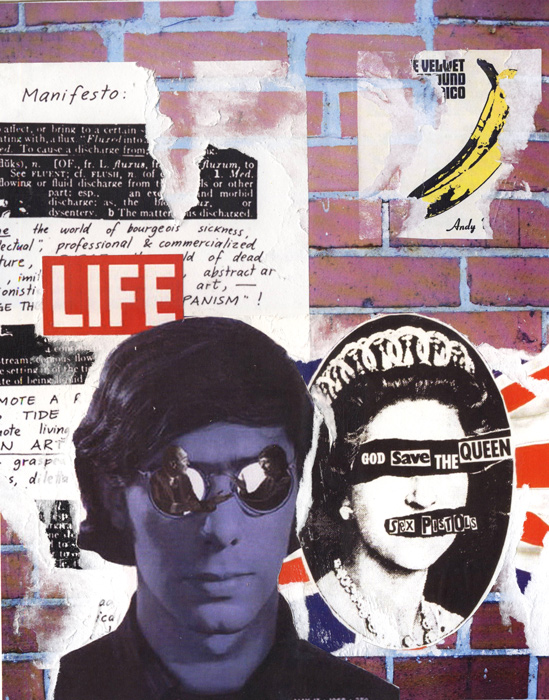

In the 1970s, a cocky successor to Dada was found in the Punk movement. Punk was a reaction against the pretentious pop music of the day. Punk rockers spat in the face of official mores and played their instruments badly. Public taste was defied both in the lyrics and the music, but also by the raw and dirty collage-inspired artwork on the album covers and in the fanzines: Collage as “up yours!”

The same spirit can be found in George Maciunas’ second Fluxus manifesto from 1965. “To justify artist’s professional parasitic and elite status in society, he must demonstrate artist’s indispensability and exclusiveness, he must demonstrate the dependability of audience upon him, he must demonstrate that no one but the artist can do art.

Therefore art must appear to be complex, pretentious, profound, serious, intellectual, theatrical…”(1)

At the beginning of the 1950s, some artists allied with consumer society, or at least its visual expression. In England after the Second World War, the craving for the American lifestyle, its shining and erotically charged consumer goods and its Afro-American music, was enormous. In this drab, brown and coal-tarnished English vacuum, Pop art emerged out of sheer necessity, and a few years later British pop music started to conquer the world. For me, collage and pop music are intimately connected. In my head, they emerged at the very same time.

In the book Collage: The Making of Modern Art, author Brandon Taylor sees the early 1960s as a period of decline for the collage. It had become mainstream, turned into mannerism and effects.(2) For me, however, who was nurtured on British pop music, this time was an intense and decisive beginning. I grew up with Life magazine. I can’t remember that I ever read it, but the pictures piled up in my head, and, as a sort of self-defence, I cut them out and turned them into collages. When the student revolt started in May 1968, I was not yet 14 years old, but I remember how Life magazine collaged Delacroix’s Marianne into a photo of a contemporary student barricade. My parents were not very interested in art, but Life provided me with ample “artistic” impressions. Quite often the magazine used photomontages to get their messages across, like on the May 17, 1968 cover where a collage by Seymour Chwast illustrates the generation gap by collaging photographs of contributors Richard Lorber and Ernest Fladell into Lorber’s sunglasses.

In 1952, the Independent Group (IG) was formed in London. They wanted to get away from prevalent artistic approaches, either modernistic or more traditional. Among its members were Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi. Pop art was born when Paolozzi held a lecture the same year and showed some of his scrapbooks with collages made from American magazines. Eduardo Paolozzi, a Scottish-born Italian, was knighted in 1988 by the Queen for his efforts.

According to Paolozzi, these magazines were a catalogue of an “exotic society, bountiful and generous where the event of selling tinned pears was transformed into multi-coloured dreams, where sensuality and virility combined to form, in our view, an art form more subtle and fulfilling than the orthodox choice of either the Tate Gallery or the Royal Academy.”(3) “I used to cut out a lot of bizarre images, out of magazine…you go beyond…a kind of pre-conception, you go beyond something that is impossible to imagine. I like to take that job–beyond my capabilities.”(4) “The word collage is inadequate because the concept should include damage, erase, destroy, deface and transform – all parts of a metaphor for the creative act itself.”(5)

For Paolozzi, the subversiveness of the collage method was not used as a rejection of society, but as a repudiation of high brow art, an art not in line with a new postwar era. Both Dada and Pop art emerged after world wars. Out of the destruction something new had to emerge. The world was torn apart, buildings were crushed, beliefs were lost in the rubble. Collage seems to be the perfect technique to capture all these raptures and dislocations. There is a direct connection between Paolozzi and Dada.

Kurt Schwitters fled to Norway in the late 1930s and in 1940 he managed to get to England. He had a hard time in London, where German artists were not en vogue. But after the war, in 1946, he had a solo exhibition, which Paolozzi saw and expressed his thoughts about them:

“Schwitters made his collages (most likely) according to the laws of chance—very much part of recent art history. Although one must retain the image of raw material—rejected rubbish such as used bus tokens—the dynamic part is the commitment of finally sticking down the objects. The excitement truly comes when the artist at that moment actually goes beyond his own preconceptions and aspirations.”(6)

“Schwitters made his collages (most likely) according to the laws of chance—very much part of recent art history. Although one must retain the image of raw material—rejected rubbish such as used bus tokens—the dynamic part is the commitment of finally sticking down the objects. The excitement truly comes when the artist at that moment actually goes beyond his own preconceptions and aspirations.”(6)

Another knighted British pop art artist was Peter Blake. Blake will forever be associated with The Beatles for his design of the Sgt. Pepper album cover. The connection between Pop art and pop music does not stop there. The cover of the next Beatles album, the so-called white album, was made by another IG member, Richard Hamilton. The same eclectic mix of styles which the collage technique so readily suggests also came to define British pop music starting in 1966 and several years beyond. The aesthetics of the collage were very much in accordance with the times.

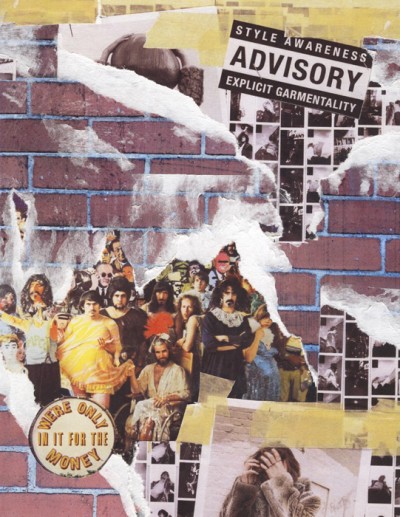

In the USA, Andy Warhol designed the cover for the album The Velvet Underground and Nico, released in 1967. Another American cult figure, musician, composer, and satirist Frank Zappa, consciously used collage or montage techniques, and Cal Schenkel, who did many of his album covers, was a congenial interpreter of Zappa’s aesthetics with his dadaistic leanings. We’re Only in It for the Money, a 1968 album by Zappa’s band The Mothers of Invention, was designed as a mean parody of Sgt. Pepper. All of a sudden, The Beatles appeared very Victorian.

With Punk, collage returned to pop music with a vengeance. The “do it yourself” aesthetic fit the Punk attitude like hand in glove. Its collage-like “ransom note” typography became trendsetting and signaled something raw and furious. In 1977, Malcolm McLaren became the manager of The Sex Pistols, whom McLaren met at his SEX shop in London’s Chelsea district in 1975. He had the group perform on a boat on the Thames at the Houses of Parliament during the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. It was a great scandalous success that resulted in McLaren’s arrest. McLaren was no ordinary shopkeeper; he was a manager, fashion designer, and anarchist. In 1968, he was unable to travel to Paris to join the student revolt. So, instead, he occupied the Croydon Art School with Jamie Ried and others.

Jamie Ried would later design all of The Sex Pistols’ record covers and singlehandedly give Punk its collage-like graphic profile. At the end of the 1960s, McLaren became interested in the situationist movement in Paris and in its London-based faction King Mob, which tried to provoke social change with different forms of action. The main target was the capitalistic consumer economy. To what degree McLaren was involved with King Mob is hard to tell, but they did share the same inclination for provocation. But idealistic? Hardly! McLaren did his best to hold on to the money The Sex Pistols generated. Johnny Rotten, the singer, had to go to court in order to get it. Maybe he “was only in it for the money”?! Malcolm McLaren died in 2010. He was not knighted.

Still today, collage signals rebellion and is often used in advertisements in order to sell stuff to a younger market segment. Collage today is no longer avant-garde. It is mainstream, even more so than in the 1960s. But even so, collage is flourishing, not at least on the internet and surely there are many young people, like me in the 1960s, who encounter collage for the first time and are turned on by collage’s ability to turn the world on its head. The common gets the crown.

The first cut is the deepest.

This commentary originally appeared in Issue Six. SUBSCRIBE to never miss an issue.

1. Maciunas, G. (1965). Manifesto on Art/Fluxus Art Amusement. Retrieved from http://www.artnotart.com/fluxus/gmaciunas-artartamusement.html

2. Taylor, B. (2004). Collage: The Making of Modern Art. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 195

3. Robbins, D. (2001). The Independent Group: Postwar Britain and the Aesthetics of Plenty. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. p. 192

4. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=436A0W_skHg (deleted)

5. Paolozzi, E. (1977). Collage, or a Scenery for a Comedy of Critical Hallucination. In Eduardo Paolozzi, Collages and Drawings. London: Anthony D’Offay Gallery.

6. Paolozzi, E. (1987). Sculpture and the Twentieth Century Condition. In R. Spencer (Ed.), Eduardo Paolozzi: Writings and Interviews. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 272

Artwork by Benoit Depelteau