Ellen Gallagher at Tate Modern

Exhibition Review by Ariane Fairlie

Note: “Ellen Gallagher: AxME” is at Tate Modern in London through 1 September 2013. Running concurrently is her first New York museum retrospective, “Ellen Gallagher: Don’t Axe Me” at the New Museum of Contemporary Art through 15 September 2013.

The most challenging part of writing about art is that much of what any artwork confronts through image is difficult (if not sometimes impossible) to adequately transfer into words and language. In fact, if it were so easily done, then artists might not feel so compelled to hash out their thoughts and feelings on paper, canvas, or any other of the limitless types of materials available to them. Ellen Gallagher’s visual language is not easily translated into words, but it is obvious that she has built a strong vocabulary to explore her concerns.

A major retrospective of Gallagher’s work is on at the Tate Modern until September, where a great deal of her collage work can be seen. Gallagher is fluent in many mediums, from painting and drawing to installation and video, but collage lends very well to much of her content and the way in which she appears to process and produce. “Minimalist” is a word that often appears in the context of Gallagher’s artwork, in reference to her use of grids and repetitive and refined imagery. The grid originated with her use of “penmanship paper,” ruled paper that children use to learn to write.

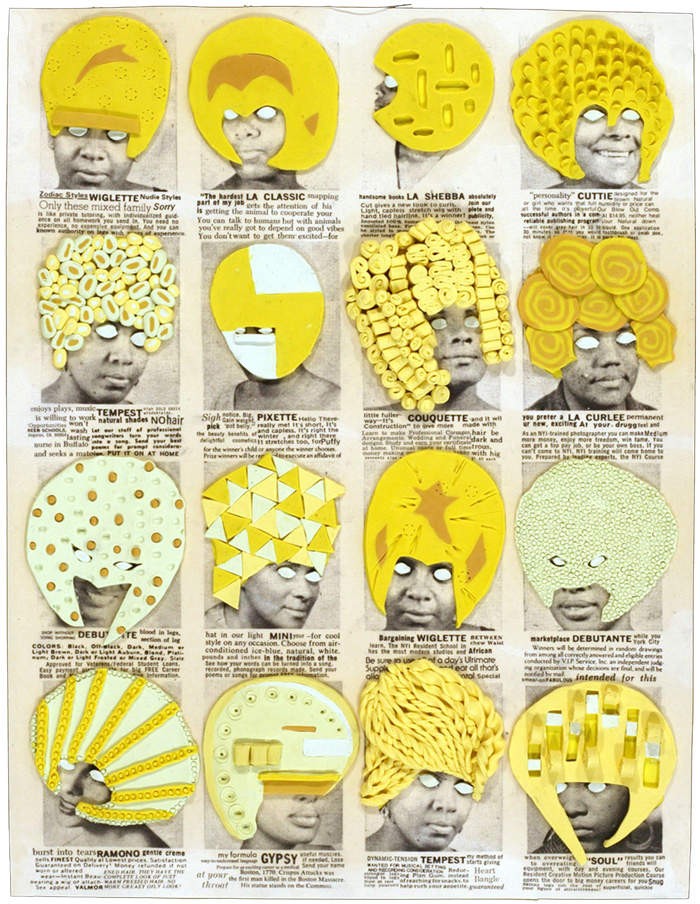

Gallagher’s self-imposed restrictions allow her to create infinitely within her own constraints. This is especially demonstrated in her Plasticine collages, dubbed “yellow paintings.” The artist accumulates a grid of found images from magazines such as Ebony, Our World, Black Stars, and Sepia, dating from the 1940s to the 1970s, and creates wig after wig of spiraling, circling, piling, helmets of blonde plastic. The images she uses in these particular pieces are taken from advertisements for hair, beauty, and skin products, and she locates the important role that hair plays in relation to race and identity.

Gallagher manages to explore these issues gracefully. Although her voice is a strong presence in all of her work, it does not critique the issues she confronts or demand the viewer to, either. She has referred to her artwork as benign, denying titillation, provocation, or any intention of really moving the viewer. It is for this reason that it is difficult to locate tangible meaning within her language; as soon as the viewer feels that they have deciphered a portion of her symbolism, it slips through their fingers.

Reading or watching interviews of the artist shows that the way she works is a reflection of how she speaks, and the reverse. She shares details of her life and work, but it is difficult to hold her to one categorization or another. She draws parallels between unexpected entities, and it seems the point of her collage is to change the context of an image without fully erasing the original character. She will often refer to her characters as “conscripted,” chosen by her without their consent, brought into another time and assigned new meaning, but simultaneously preserving a piece of their past identity.

The experience of the artwork feels familiar, the meaning obvious or easily accessed, due to the subject matter she references and materials she uses. Within any given artwork the viewer can observe the finite development of her vocabulary through reoccurring and evolving patterns. Still, as you witness Gallagher’s inner dialogue it is clear there are no definitive answers, and certainly that it is an ongoing and consuming journey.

The exhibition itself is not set up in chronological order, but instead, tracks different themes found within Gallagher’s work. She draws inspiration from marine biology, science fiction, eye and mouth features referring to minstrels and blackface, as well as music and advertisements from around the same era as her source material. Rhythm is essential to Gallagher’s work as she repeats and augments forms. The artworks are contemplative in their obsessive and labour-intensive treatment, and the rhythm can feel organic as she diverges more from the grid with loose patterns of eyes punctuated by lips, or more automatic, as each scale of a fish is lifted meticulously from a page of thick white paper.

What distinguishes Gallagher is her thorough probing of each of her subjects and the repetitive nature of her research. She brings together marks, forms and content that would not make sense on the surface, were it not for her continual and minimal adjustments and recontextualizations. She seamlessly connects underwater worlds and events from our cultural subconscious, or combines furry alien spaceships with sphinxes implanted with the eyes and lips so often repeated in her work. As you are immersed in Gallagher’s world, each detail of her vocabulary becomes significant, to the point where the introduction of an ear reverberates through your understanding, causing you to reassess her symbolic system as it once again escapes palpable grasp.

This review appeared in Issue 5 of Kolaj Magazine. To get your own copy or to subscribe, visit http://kolajmagazine.com/content/subscribe.

INFORMATION

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG United Kingdom

(0)20 7887 8888

Hours:

Sunday-Thursday, 10AM-6PM

Friday-Saturday, 10AM-10PM

Image:

Wiglette from “DeLuxe”

by Ellen Gallagher

photogravure and Plasticine

2004

© Ellen Gallagher

Courtesy of Tate Modern, London